A bulletproof vest is often called a ballistic vest or bullet-resistant vest. It is an item of personal armor that is used to protect the human body. It also absorbs the impact and reduces or even stops the penetration to the human body of firearm-fired projectiles, and explosion shrapnel.

These bulletproof vests often have a bulletproof layer inserted into the outer vest. The outer vests are usually made of chemical fiber fabrics. The bulletproof layer is made of metal (special steel, aluminum alloy, and titanium alloy), or ceramic plates (corundum, boron carbide, silicon carbide, and alumina), glass reinforced plastic, nylon, Kevlar. Other components include ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene plates, liquid protective materials, and more, which form a single or composite protective structure.

Metal or ceramic plates can provide additional protection against rifle rounds. Metallic components or tightly woven fiber layers can give a soft armor resistance to stab and slash attacks from knives and similar close-quarter weapons. They can also help reduce the damage to the chest and the abdomen of the human body when affected by a recess.

As a protective item, the core performance indicator of a bulletproof vest is its anti-elasticity. At the same time, as a functional clothing, it should have the characteristics of ordinary clothes.

The ballistic performance of bulletproof vests is mainly represented by the following two aspects:

(1) Anti-ballistic protection:

One of the main threats on the battlefield are high-speed fragments from various explosives such as bombs, mines, shells, and grenades. The most dangerous threats faced by soldiers on a battlefield are in order shrapnel, bullets, blast shock waves and heat. Therefore, a bulletproof vest should be extremely anti-ballistic to ensure a life-saving protection.

(2) Anti-penetration damage:

Bullets can create a significant impact after hitting a target. The damage caused to the human body is often fatal. It will cause internal injuries, which can be life-threatening. Therefore, preventing non-penetrating damage is also an essential aspect of reflecting and testing the ballistic performance of bulletproof vests.

Indepman Bullet-proof Vest Manufacturing Process:

Step 1: Making the panel cloth

To make Kevlar, the polymer poly-para-phenylene terephthalamide must first be produced in the laboratory. This is done through a process known as “polymerization”, which involves combining molecules into long chains. The resultant crystalline liquid with polymers in the shape of rods is then extruded through a spinneret (a small metal plate full of tiny holes that looks like a shower head) to form Kevlar yarn. The Kevlar fiber then passes through a cooling bath to help it harden. After being sprayed with water, the synthetic fiber is wound onto rolls. The Kevlar manufacturer then typically sends the fiber to throwsters, who twist the yarn to make it suitable for weaving. To make Kevlar cloth, the yarns are woven in the most straightforward pattern, plain or tabby weave, which is merely the over and under the pattern of threads that interlace alternatively.

Step 2: Cutting the panels

Kevlar cloth is sent in large rolls to Indepman. The fabric is first unrolled onto a cutting table that must be long enough to allow several panels to be cut out at a time; sometimes it can be as long as 32.79 yards (30 meters). As many layers of the material as needed (as few as eight layers, or as many as 25, depending on the level of protection desired) are laid out on the cutting table.

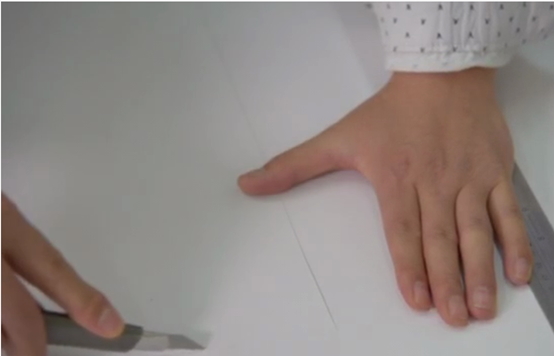

Next, a cut sheet, similar to pattern pieces used for home sewing, is then placed on the layers of cloth.

Using a hand-held machine that performs like a jigsaw except that instead of a cutting wire it has a 5.91-inch (15-centimeter) cutting wheel similar to that on the end of a pizza cutter, a worker cuts around the cut sheets to form panels, which are then placed in precise stacks.

Step 3: Sewing the panels

While Spectra Shield generally does not require sewing, as its panels are usually just cut and stacked in layers that go into tight-fitting pouches in the vest, a bulletproof vest made from Kevlar can be either quilt-stitched or box-stitched. Quilt-stitching forms small diamonds of cloth separated by stitching, whereas box stitching forms a sizeable single box in the middle of the vest. Quilt-stitching is more labor-intensive and complicated, and it provides a solid panel that is hard to shift away from vulnerable areas. Box-stitching, on the other hand, is fast and easy and allows the free movement of the vest.

To sew the layers together, workers place a stencil on top of the layers and rub chalk on the exposed areas of the panel, making a dotted line on the cloth. A sewer then stitches the layers together, following the pattern made by the chalk. Next, a size label is sewn onto the panel.

Step 4: Finishing the vest

The shells for the panels are sewn together in the same factory using standard industrial sewing machines and standard sewing practices. The panels are then slipped inside the shells, and the accessories—such as the straps—are sewn on.

The finished bulletproof vest is boxed and shipped to the customer.

Step 5: Quality Control

Bulletproof vests undergo many of the same tests a regular piece of clothing does. The fiber manufacturer tests the fiber and yarn tensile strength, and the fabric weavers test the tensile strength of the resultant cloth. Nonwoven Spectra is also tested for tensile strength by the manufacturer. Vest manufacturers test the panel material (whether Kevlar or Spectra) for strength and production quality control requires that trained observers inspect the vests after the panels are sewn and the vests completed.

Bulletproof vests, unlike regular clothing, must undergo stringent protection testing as required by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ). Not all bulletproof vests are alike. Some protect against lead bullets at low velocity, and some protect against full metal jacketed bullets at high velocity. Vests are classified numerically from lowest to highest protection: I, II-A, II, III-A, III, IV, and special cases (those for which the customer specifies the protection needed). Each classification specifies which type of bullet at what velocity will not penetrate the vest. While it seems logical to choose the highest-rated vests (such as III or IV), such vests are bulky, and the needs of a person wearing one might deem a lighter vest more appropriate. For police use, a general rule suggested by experts is to purchase a vest that protects against the type of firearm the officer carries typically.

The size label on a vest is critical. Not only does it include size, model, style, manufacturer’s logo, and care instructions as regular clothing does, it must also include the protection rating, lot number, date of issue, an indication of which side should face out, a serial number, a note indicating it meets NIJ approval standards, and—for type I through type III-A vests—a significant warning that the vest will not protect the wearer from sharp instruments or rifle fire.

Bulletproof vests are tested both when wet and dry. This is done because the fibers used to make a vest perform differently when wet.

Testing (wet or dry) a vest entails wrapping it around a modeling clay dummy. A firearm of the correct type with a bullet of the correct type is then shot at a velocity suitable for the classification of the vest. Each shot should be three inches (7.6 centimeters) away from the edge of the vest and almost two inches from (five centimeters) away from previous shots. Six shots are fired, two at a 30-degree angle of incidence, and four at a 0-degree angle of incidence. One shot should fall on a seam. This method of shooting forms a wide triangle of bullet holes. The vest is then turned upside down and shot the same way, this time making a narrow triangle of bullet holes. To pass the test, the vest should show no sign of penetration. That is, the clay dummy should have no holes or pieces of vest or bullet in it. Though the bullet will leave a dent, it should be no thicker than 1.7 inches (4.4 centimeters).

When a vest passes inspections, the model number is certified, and the manufacturer can then make exact duplicates of the vest. After the vest has been tested, it is placed in an archive so that in the future vests with the same model number can be easily checked against the prototype.